by Emily Johnson

Published in UN PROJECT's Un Magazine 14:1, 2020

My Grandma Hanna made the wallet I carry with me every day. It’s tanned caribou hide, trimmed with small green and white glass beads, a perfect five-petal flower — dark green, iridescent orange, with a light-pink centre. It’s sitting next to me as I write this from Lenapeyok homeland, Lenapehoking. I carry my grandma’s gorgeous wallet with me, proudly lay it on the table or bar when I am about to pay. People always ask. And I smile. I get to tell them Grandma made it. And I get to tell them she won a blue ribbon at the state fair.

It needs some repair. A small hole has emerged on the back left corner. I should apply some oil to the hide, re-stitch one of the Velcro bits that holds the rounded flap down. Charlie Stately, who runs Woodlands Indian Crafts at the American Indian Center in Mni Sota Makoce (Minneapolis, Minnesota) made a repair once, stitched a few of the beads pulled loose from the trim.

I’ve lost Grandma’s wallet twice.

The first time, it fell out of my pocket as I climbed from a car. I could see it in my mind, laying by the tyre. I ran, reached the curb and cried, not for anything inside, but for the caribou hide, the beaded flower, my grandma always near.

Someone found it. Simpson Housing, an organisation serving people experiencing homelessness, called to let me know a client of theirs had my wallet. He saw a commonality between us and wanted to give it back, directly to me. I said, ‘Of course! When is he there?’ She said, ‘We never know.’

I went to Simpson Housing a few times, brought a gift card, left notes, kept hoping to run into the man holding onto Grandma’s wallet, a man whose name I couldn’t know. Our time never coalesced. Or maybe he never went back. Or maybe I gave up too early. I eventually stopped making the trip across town.

Two years later Grandma’s wallet came back to me in a package from Simpson Housing. Everything that had been in it was inside. I called. There was no one to explain.

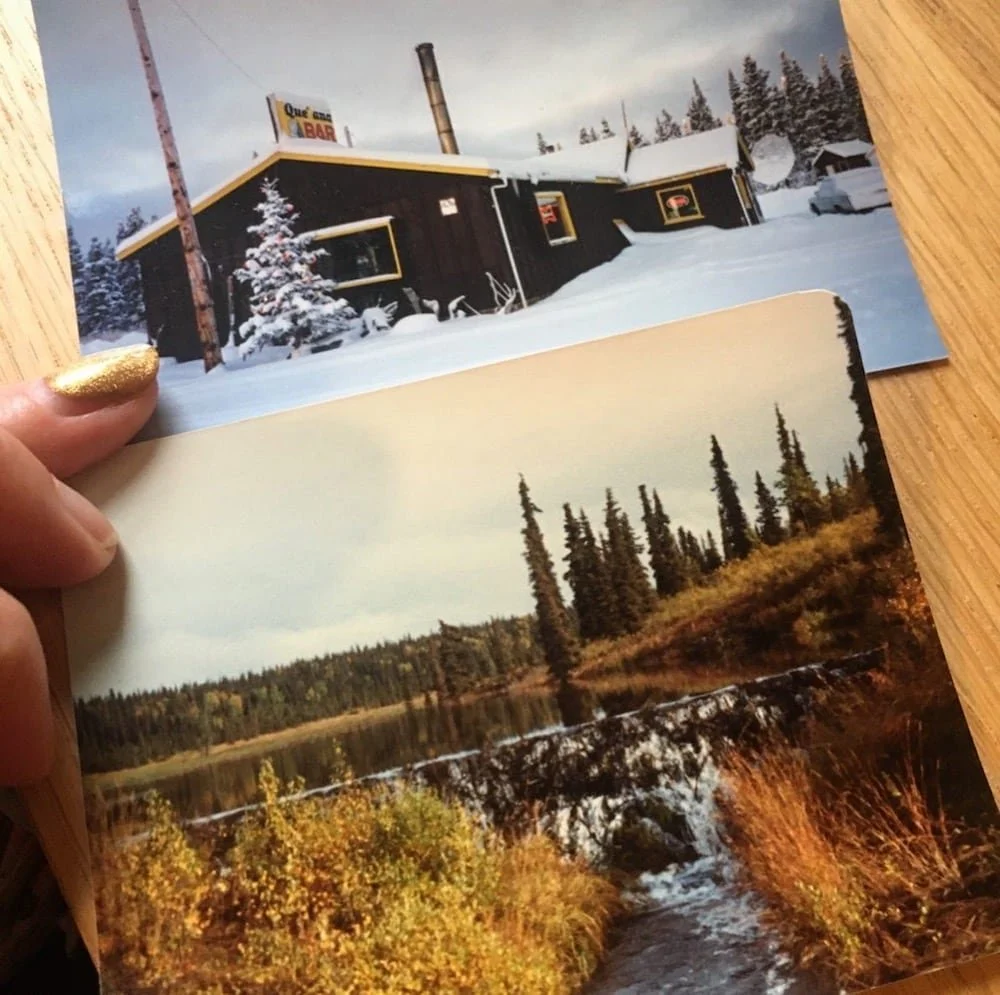

A while after this, in Dzidzelaľic̆/Dkhw’Duw’Absh (Seattle), I was making a dance called The Thank-you Bar and improvising, my eyes closed. The Thank-you Bar is named after my Grandma Hanna’s roadside bar in Alaska, The Que-Ana Bar, and I made it during a period of intense homesickness.

Looking back, I think I was understanding I wouldn’t be moving home to Alaska again. I was searching, internally and externally, for the reasons why, for the implications, decisions and impacts of displacement — chosen in my case, or forced in many others’. I was in longing for home, of home.

I was thinking of language, of why Grandma chose to name her bar Que-Ana — after the Yup’ik word, quyana, thank you. How she kept and asserted a spoken part of our culture with her naming of the bar. Why did she choose phonetic spelling? Because her customers down on the Kenai Peninsula, away from Yup’ik homeland, are not Yup’ik? Because Que-Ana is easier to see or say than quyana? Or, was it not intentional at all, because while Yugtun is her first language, she learnt it before it was written down?

I always loved this Yup’ik oasis, named in and for gratitude. And I’ve always been grateful for the bar, even though some rough stuff happened there too. Grandma’s house and bar, where we cleaned and smoked our fish, where we gathered to hunt, where great-Grandma Lena played solitaire, when visiting, where there was almost always a scrabble game on, where all my cousins and brothers would run up the hill in summer, sled down it in winter. Making The Thank-you Bar, I was thinking of family and culture and (intended) miscommunication, asserted values, preconceived notions, and the effects of a dominant language on a land with multiple Indigenous language realities. I was also thinking about the beaver lodge across the road, the beavers I would watch and study all my growing up until the state came and knocked down their dam. I was thinking too of architecture — lodges and bars and igloos — and how we build our homes and communities where we find ourselves. How do we do that?

I asked a bird researcher at Florida State University, ‘what happens to the birds when we knock down their trees?’ Expecting a more esoteric answer, she said, ‘they move homes. They rebuild their nests.’ I suppose the beavers did this too. There were times, making The Thank-you Bar, I would shut my eyes, imagine dancing on the small dance floor at the Que-Ana Bar, near the pool table, across from the fireplace, to the country music from the jukebox, under the sparkling ceiling probably made of asbestos. I absolutely tried to be in two places at once, to build that internal muscle I know is there from my time and space travelling ancestors — I got it, sometimes. I could be back ‘home’ at Grandma’s bar, and be dancing in the studio too.

Maybe it was one of these moments, when I was preoccupied with space and time travel, that a stranger came into the studio in Dzidzelaľic̆/Dkhw’Duw’Absh. He knelt beside my tote bag. I rewound the video camera and could see him – reflected in the mirror behind me — kneel down, reach inside and take the clutch, Grandma’s wallet inside, as I danced.

Weeks later I opened a small package from the Seattle post office. Accompanying Grandma’s wallet was a handwritten note: ‘This happens, sometimes people take what they want, throw the rest in the postbox. It’s our policy to return what belongings we can.’

Sometimes I stuff Grandma’s wallet too full with receipts and coins. I empty it, smooth the corners, tend the beads, rub the caribou hide. I tell the story of how it has gone missing and found its way back, twice. Grandma likes this story too.

I’ve never asked Grandma why she didn’t teach us Yungtun. As I look at the post-its fading next to me on my wall — ellangengcinartua, gradual process of becoming aware; agayu, to pray; elpengengnaqi, an encouragement to gradually seek acquisition of the senses, feelings, mind; qaneq, mouth — and as I note I haven’t opened my Yungtun app in weeks, I suffer in how learning language as an adult frustrates me and makes me wish I knew from a young girl how to move my mouth and throat correctly, how to speak to my ancestors in their language, how to introduce myself or speak words to concepts I know in my body. I get impatient with myself and I suppose with Grandma, too. I wish I had been taught.

But I also remember Grandma giving me my first Yungtun dictionary as I stood to bow after the premiere of The Thank-you Bar in Dena’ina Ełnena (Anchorage, Alaska). And I think of how I’ll call her now, ask pronunciation or meanings of words. I remember how as soon as we step off the plane into Mamterilleq (Bethel), she’ll start speaking language and say how good it feels. How sometimes she’ll sing in language. It took me some time to recognise Grandma’s refusal to teach her kids and grandkids’ language as an act of care. And this is how I think of it now. It was the way she had been taught — to protect. An extension of care in the absence of teaching, (a mind-fuck, really, for those of us with less patience) and truly only a pause until, at least for our family, the radical resurgence, as Leanne Betasamoskake Simpson calls it, can (begin to) occur, can root in our mouths and our bones, can call us to refuse to not know any longer.

**

My cousin Ducky and I like to get together with Grandma to make akutuk, a sweet mixture of whipped seal oil or Crisco, berries, sugar, whitefish. We bring my niece Kaia if we can, teach her as we also learn. With my friend and collaborator Jen Rae, a brilliant Narrm (Melbourne) based artist-researcher, I made this delicious dessert in 2017 for the occasion of SHORE: FEAST in Narrm. We were after an Alaskaustralia akutaq of sorts. With cousin Ducky, my mom and Grandma on the phone, we worked in the downstairs kitchen at ArtsHouse trying to find the right consistency, colour and flavor with rainforest cherry, lilly pilly, muntries, bush honey and whiting in place of blueberry, salmon berry, sultanas and whitefish. The whiting so much smaller than whitefish, with so many more bones, the bush honey a dark colour that changed the tone until we whipped it enough, the Crisco difficult to find in Australia save ex-pat and dear friend Nancy Black, who knew where to get it. Our efforts and the challenge and idea of sharing something from home merged with Jen’s skill and determination and the collaborative effort of us all, including the elderly Italian man who harvested and delivered prickly pears for the sweet reduction we needed. Nothing makes me proud as offering something my grandma taught us to make.

We surge forward with what we are trying to build and make and learn and remember with the efforts our grandmas and ancestors give or gave or held back out of necessity.

I smiled every time someone came back for seconds of the ‘fish ice cream.’

Grandma likes this story too.

When I stood at the front lines at Oceti Sakowin, for Oceti Sakowin, with fellow water protectors facing bullets, water hoses, arrest and heartbreak at the fact we have to protect what is ours in the first place, I raised up my arms. My fellow protectors led in song and strength and called upon colonising trespassers to leave sacred ground and we all lifted our arms to show we had no weapons.

Along with my fellow protectors I danced right foot and left foot, right foot and left foot, with my arms raised up. I looked at each of the men standing above us on the hill, riot gear on, visors pulled down, weapons and hoses drawn and I saw anger and I thought about the people who love them, because surely they exist. I asked each of the men to feel love, to connect with love, to look at us with love. I knew each of those men had a choice. They could put their guns down. They could turn around. They could go home. They did not choose this.

I remember our singing in the face of violence.

I remember our arms raised.

We were on that front line a long time. It was cold and tense. When I think back to that extended time on that river bank I feel a protection around us – the songs, the smoke, the prayers and love offered.

And when I think of this love offered I come so close to grief.

There is so much to grieve.

My grandma told me she was not allowed to attend yuraq, dance, in the village where she grew up. She said, ‘Mama didn’t let us go.’ She was allowed to watch the dancers practice and sometimes she made the trip across the river with her mom and sister in winter to do so. But when the village gathered for yuraq, ‘when we would ask her if we could go she said, “no, you can’t go.”’ Her mother never explained it, she just said, ‘no, you can’t go.’ In 1994, when Grandma and I went to Yupiit Yuraryarait dance festival in Negeqliq (St. Mary’s, Alaska) it was the first time she had seen yuraq in decades.

How do we feel that rub of love and grief?

‘Mama didn’t let us go.’

How do we let that propel us to good action?

‘Put down your guns.’How do we say each day - I am sorry?

How do we say each day - I forgive you?

And what from that might spark?How do I hold my hands and my arms up to my enemy?

Not in surrender.

Not to show I have no weapons.

But in surging, surgent love?

A love that brings forth every bit of change we need to see.

**

There is a dance I want to make that moves the world. It moves the audience, makers and performers from ‘stage’ to continued action and work in the world and future. Not as in ‘inspire’ and not as in ‘guide.’ I want to make a deep structural change and consciousness shift — a community centred coalition of allyship that centres Indigenous brilliance, that is justice, that is equity in action. I speak of dances as gatherings. I speak of performing as offering. I see dance as vital in the world because we are — human and more than human, star and constellation, fire and tree, all oceans and water, ancestor and future ancestor, thought and Indigenous led knowledges — moving, surging.

As I typed that last sentence, The New York Times announced that Harvey Weinstein is guilty on two charges.

It is not easy work, this Indigenous, surgent love.

The first time I was raped was in a tent. I’ve slept in many tents and I love the heat that builds in them overnight. Just the sleeping heat. The tent we had when I was a kid was army green and huge. We most usually camped by the ocean, my brothers and I and our cousins falling asleep to the sounds of waves and our adults laughing outside at the fire. I also love how rain hits tents, softly. How the zipper sounds. The light in the morning. The immediate intimacy of bedroll, sleeping bag, and that nothing else is there. Just bodies, and in the best camping, bareness.

The other night, I stepped into a hotel elevator filled with five men. I am not afraid of men and I’m also not not afraid of men. I said hello to the still air. I looked them each in the face. When I stepped out at my floor the guy who had been in front of me and to the left, facing me with his back to the north side of the elevator, yelled out his room number. I heard one of the other guys say, ‘dude, you’re a dick.’ Someone else laughed and I can say that I despise this moment — this moment this man took space and air from the world to extend his assuming callous dismantled remorseless raping conquering taking taking taking thoughts to me at me as if anything he wanted to take he could take, as if anything he wanted could be smattered by his disgusting self and left on me, in me. The back of my neck became a neck that is not mine. It is not my neck anymore or ever again. It is not my neck to feel shame put upon it, to droop down so low that my forehead curls into my chest, so low that my chest curls into my belly, curling, huddled into itself, drowning in his voice and sounds. That is not my neck, not my body, not my hatred, not my drowning.

My body.

My body comes from generations and generations and generations of love. My body comes, also, from men who took, who raped, who tried, above all else, to conquer. But my body, more than anything, comes from women. Women who unfurl again and again, heated, unaccepting of force and forced rage, who in their own wisdom direct their anger and grief to movement, action, peace.

My grandma was not allowed to attend yuraq and there was no explanation offered. Grandma can speculate that perhaps it was the distance, that trip across the river; perhaps the time commitment would have taken a toll on the family; perhaps it was because her mom didn’t know how to dance (she said that one with a laugh!). I wonder, too, was her mom’s refusal also a form of protection? An extension of care through absence, again, until my grandma could, with me, her granddaughter, share yuraq in Negeqliq? Where we could surge forward together, feasting with relatives and community. Where as a young choreographer I could begin, just barely, to sense and see the power of yuraq — the surging love through days of dance, the calls of pamyua! (calling the dance to start again). This time with Grandma has fed me for over twenty years and I wish I knew yuraq, I long for it. From my place in the world, I know it is my responsibility to assert dance as vital. To assert equity. To learn. And to center Indigenous stories, voices, artists, knowledges and processes.

There is a dance I made called Then a Cunning Voice and A Night We Spend Gazing at Stars. It’s fifteen hours long, from sundown to sunrise, outdoors, on eighty-four hand-sewn quilts made in sewing bees on Turtle Island, in so-called Australia and Taiwan. It focuses attention on the space we share, the histories we hold, and how we might envision our futures, together. It relies upon individuals coming together to witness, work, experience time, rest, imagine and voice intentions with a particular attention to the Indigenous land and aqueous spaces we occupy. It requires a deep extension of care and a reciprocal request for commitment — to one another and to the place upon which we are gathered.

There is a moment in this dance when I ask someone to kiss the back of my hand, my fingertips, my shoulder blades. There is a moment when I ask someone to hold my arms. Someone I love told me once they didn’t like this moment. They thought it might be, in this performative setting, not a real interaction. As in who, attending a fifteen-hour all-night performance about collective intentionality, would say no?

I understand this point. Or, rather, the deeper problem behind the point. There are times in performance when an interaction is not real, when care is not offered, when consent

is not respected or required. I don’t mean performance needs to be careful. Quite the opposite. Performance needs to be so radically involved in collective consciousness that it can shift said consciousness, that it can be a catalyst for change. When performance is not real, then it is performed. Just as solidarity, when performed, is not real but dangerous, usurped into, as Eve Tuck describes, ‘settler moves to innocence.’

My grandma was not allowed to attend dances.

Our dances are healing, they are medicine, they are communal, they are real.

Emily Johnson, 'Then a Cunning Voice and A Night We Spend Gazing at Stars' (performance still), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist and Tulsa Artist Fellowship. Photo: Melissa Lukenbaugh.

**

When we returned from the day of direct action at Oceti Sakowin, our camp leader, Candy Brings Plenty, guided us to gather at the fire. We thanked one another, honoured our intentions, guidance from Elders, and especially those who stayed back to keep the fire going, to make soup for when we returned.

There are two times I most vividly remember my arms being held. In Dena’ina Ełnena, Nadia Jackinsky Sethi stood up. Nadia and I have spent a small amount of time together in Quinhagak, Alaska. We shared a walk there, time with the Bering Sea, and time with kids, Elders, and cultural belongings of Nunalleq. A Sugpiaq art historian, Nadia knows and leads cultural rematriative efforts and brings arts activities to Alaska Native communities through her work with CIRI Foundation. Nadia and I don’t know each other all that well yet, but when I asked someone to hold my arms and then walked to her, my arms outstretched, she wrapped her hands beneath my upper arms, held their weight. She relieved me for a moment of all I hold. She offered a knowing power. We looked at one another, I recall this vibrant feeling, a grounded sadness, a drawn breath, an un-worded moment of seeing one another and time — the knowledge real seeing brings moved between us. An Indigenous woman holding another Indigenous woman’s arms for her because she asked. In the offering to hold we reciprocated in love. I feel deeply committed to Nadia. If she called me from Alaska today and needed me to hear her or hold her or send an email or take a selfie or tell her a joke or answer a question, I would. I want to reciprocate Nadia’s care for me.

In Tulsa, a very young, very small child stood up. She walked to me, silently. She reached up her arms and I knelt down so she could hold mine. She went up on her tiptoes. She looked at me and she let my arms rest in her hands for a long time. I said thank you. And I could not have been more moved.

What is it that calls us to love?

To be love. To generate love with one another and beyond one another.

What calls us to the front lines of loving, of change, of protection?

I was standing with a saguaro about five years ago and after quite a while this saguaro asked me what it is like to have arms. I cannot tell you this whole story, but I can tell you that I described my arms as coming from my back, that I feel as though my shoulder blades are wing joints, that I imagine the joint where the scapular feathers of the wing of a hawk meet the glenoid fossa and the trioseal canal is where my scapula is. And I feel as though my arms move forward, from my back, that they hold. And I said that I feel tenderness through my arms. And power through my arms. That it is amazing to hold someone who is dear to you, close to you, in your arms. That holding small, tiny beings and things feels similar somehow to holding larger, weightier, more complicated beings and things. That action comes from these tiny finger tips and that, from them, you can begin doing things, like, moving dirt.

And then, complete awareness. An awareness and a way of standing from the inside of my body, with no centre, no regulation of centre or edge, or front or back. A roundness with an understanding that as a human is hard to put words to but I’ll try. It was like no edge. No seeing, no need for orientation. The stars were there and the ground was there and the deepest inside of my body was also outside of my body but in a way I was still whole. If there were a word in the English language for equality with abundance and a knowledge of past, present, and future that makes that equality have greater weight — that would be the word. That saguaro stands with thousands of its relatives. And like us, they are there and they are there and they are there. Standing. And there is no direction. But there is equity. And reverence. And relation.

We had a long continued exchange, that saguaro and I. And then in the silence, the true, honest silence we shared being, standing and eons. My arms were at my sides and the saguaro spines stretched into the air.

I remember this moment.

I remember our singing in the face of violence.

I remember the first Yup’ik word I knew, quyana.

I champion all of us at all of the front lines.

And I champion our allies who become accomplices.

We build kinstillatory relations. We sing and raise our arms and make plays and dances and artworks. We gather and write. We curate and share. We protect, we deliver. We build fire and make soup. We build worlds and we listen. We learn when our Grandmas and ancestors are ready to teach us. We break down the literal and figurative walls colonisers built, build and hide behind to destroy us.

Grandma has always been teaching me Yungtun.

And the present future?

Violence has no place here.

Thank you everyone who returned Grandma’s wallet to me.

Thank you everyone who is surgent love. We refuse to not know it any longer.

I remember.

I remember.

Quyana.

Thank you to Karyn Recollet for our ongoing collaboration, and her continual thinking on the concepts of kinstillatory.