PRESS

“A magnetic performer, adept at mobilizing people, onstage and off...”

—The New York Times

PROFILES of EMILY JOHNSON

Originally from Alaska, Emily Johnson currently lives and works in New York City, though her forward-thinking productions have seen her travel both nationally and globally. An Indigenous artist of Yup’ik descent, Johnson has always been far-reaching in her work. While choreographic explorations are part of her multifaceted projects, she has been concerned with environmental and societal issues and deeply involved in audience engagement, enhancing her role as an artist with important aspects of community organizing and activism.

On an evening in early June, before the sun had gone down, a bonfire blazed outside Abrons Arts Center on the Lower East Side. Handmade quilts lined the steps of the outdoor amphitheater. Anyone walking down Grand Street could come in and take a seat.

As a group of singers arranged themselves around a large cylindrical drum, the choreographer Emily Johnson stood up to speak a few careful, welcoming words.

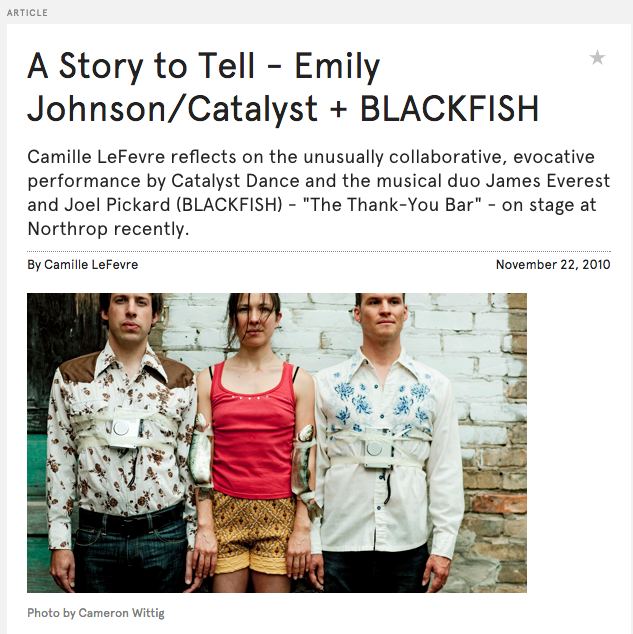

Dancemaker, choreographer, and storyteller Emily Johnson combines personal stories and powerful movement in her latest work The Thank-you Bar, which debuted in Minneapolis at the University of Minnesota's Northrop Auditorium. Johnson believes that anything can be dance: Our physical responses to the world is where dance begins. Johnson's philosophy about movement can be seen in her previous work Heat and Life, (2004) which was commissioned by the Walker Art Center to engage the controversial topic of global warming.

The November performance of The Thank-You Bar, created by Minneapolis dance maker Emily Johnson with musicians James Everest and Joel Pickard of Blackfish, didn't begin inside a theater. Instead, audience members entered a gallery space in the Northrop Auditorium building. The exhibition on view, curated by Johnson with Carolyn Lee Anderson and titled "This Is Displacement: Native Artists Consider the Relationship Between Land and Identity," set the tone for a deeply personal examination of the constants and changes that shape an individual's relationship to home.

In 2002, you could have seen Emily Johnson's Plain Old Andrea, with a Gun at the Southern Theater as part of the Momentum series. In 2004, you could have seen her Heat and Lifeat the Soap Factory, presented by the Walker. But since then, you'd have to be either lucky or savvy to catch Johnson -- she's performed primarily at various small venues (the BLB, the Rogue Buddha Gallery) or in site-specific explorations (Landmark at the Stone Arch Bridge).

BEING FUTURE BEING

“Be they in quiet or frenzy, four dancers and Johnson seem possessed but also possess power . . . Chacon’s tectonic score groans like the ground rumbling under our feet.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Merging art and activism, Johnson’s expansive work [draws] our attention to the land beneath and around us — to what has been here before and what could be in the future. She heightens our awareness . . .”

—The New York Times

FIRST NATIONS DIALOGUES

“Rather than express Indigenous art as its own sequestered genre, the point of [First Nations Dialongues] is to bring an underrepresented demographic of artists to the fore.”

—Hyperallergic

DOCTOR ATOMIC

“And nothing stopped a performance of the most significant, I’d say the greatest, opera of our time.”

—Los Angeles Times

THEN A CUNNING VOICE

“It’s a sleepover to beat all sleepovers. Food, stories, discussions, dances and, after an opening ceremony

and a two-mile walk, settling down for the night on a 4,000-square-foot bed of quilts.”

—The New York Times

SHORE

“Johnson’s works dwell in the liminal space between memoir and dream, intimate and mythical, dance and installation, continually working away at the boundaries between performers and audience.”

—Eleanor Savage, SHORE Essay

Choreographer Emily Johnson used to set herself a solid rule: never use the words "tradition" or "contemporary" when discussing her work. Simple enough, you would think, but when you're an indigenous artist - in Johnson's case, of the Yup'ik people of the Alaskan peninsula - it amounts to defying a world that wants to pigeonhole your art into one of those two categories.

Emily Johnson’s Shore, the third part of a trilogy that was preceded by the Bessie-award-winning The Thank-You Bar and Nicugni, did not consist only of the performance that appeared at New York Live Arts from April 23-25. Beginning April 19, there were related community action events (land, water, and dune restoration) in the Rockaways and on Governors Island, a curated reading of stories on Rutgers Slip in downtown Manhattan, and a final potluck feast at the North Brooklyn Boat Club. The Governor’s Island event focused on the efforts to reseed the oyster beds that once existed in the waters there. Twenty partnering organizations are listed in the program insert. For Johnson, art should not be separated from community.

At spring, people return from the wintered isolation of their respective family nuclei and form one whole organism, made up of all the parts that sustain a community. SHORE is the ambitious five-event macrocosm of the traditional Alaskan Yup'ik congregation of individual and communal spirits at this rawest leg of the solar round.

About a hundred people assembled at a basketball court on West 21st Street in Chelsea on Thursday night, huddled around a cardboard sign that read “Gather Here.” This was the starting point for “Shore: Performance,” one phase of the choreographer Emily Johnson’s multipart, multicity project, “Shore.” Following Ms. Johnson’s instructions to “walk together and in silence,” we made our way to New York Live Arts on West 19th Street, along the path (roughly) of what used to be Minetta Creek.

Covering large expanses of space and time, “Shore in Lenapehoking,” which ended on Sunday, unfolded over eight days in three boroughs, on beaches and docks, beneath highways and bridges, at a community center, a schoolyard and a theater. Lenapehoking, home of the Lenape tribe, encompasses what is now New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Pennsylvania and part of Connecticut — places, the title reminds us, that have not always gone by these names.

Emily Johnson’s Shore is another beautifully organic participatory event that brings audience and performer together with the local surroundings. The last part of a trilogy that began with The Thank-you Bar and Niicugni, Shore opens in the outdoor playground of PS 11 on West Twenty-First St., where people gather near the large-scale mural by Os Gemeos and Futura of a cartoonish character wearing shorts covered in flags of the world, which is representative of the four-part work’s inclusiveness. (There are also separate volunteer, feast, and story sections of Shore.) Attendees can go on the slide, commune with a coop of chickens, shoot some hoops, or grab one of the red blankets and huddle for warmth in these cold late-April days.

SHORE is Emily Johnson/Catalyst's new dance work. It is the third in a trilogy of works that began with The Thank-you Bar, and continued with Niicugni. SHORE is a multi-day performance installation of dance, story, volunteerism, and feasting. It is a celebration of the places where we meet and merge—land and water, performer and audience, art and community, past, present, and future.

SHORE is Emily Johnson/Catalyst's new dance work. It is the third in a trilogy of works that began with The Thank-you Bar, and continued with Niicugni. SHORE is a multi-day performance installation of dance, story, volunteerism, and feasting. It is a celebration of the places where we meet and merge—land and water, performer and audience, art and community, past, present, and future.

Northrop: When we interviewed you last spring about Niicugni, the second in this trilogy of works (SHORE being the third), you said as you’re making one work in this series, the next one begins. At what point in your process did you know what SHORE would encompass?

Emily Johnson: It was a natural progression—I remember looking around the room during one of our fish-skin sewing workshops during the making of Niicugni. I was overwhelmed with gratitude—for all of the energy and work people were donating to Niicugni through their preparations and sewing of the fish-skins. I decided I needed to continue to research this—why people come together and how the energy and actions of a group of people can have an effect on a project, on the world.

NIICUGNI

“Before the lanterned darkness empties us back out, let’s take more time to listen to these ingenious muscles, nerves, and bones that channel the migrating fish, the statuesque fox, the eternal swaggering bear.”

—Siobhan Burke, Performance Club

MOMENTS after walking into a Chelsea cafe the choreographer Emily Johnson accepted a compliment for her vintage black-and-white brocade coat. But there was a catch. “You do,” she said as her blue eyes twinkled mischievously, “have to take it off awkwardly.”

Emily Johnson at the Baryshnikov Arts Center, where her work will appear.

Ms. Johnson slipped her arms out of the sleeves, lowered the fabric to the floor and stepped out of it.

“It’s really a dress,” she said.

Fittingly, Ms. Johnson’s richly detailed dance-installations are full of surprises too. A Minneapolis artist originally from Alaska, Ms. Johnson returns to New York to present “Niicugni,” the second piece in a trilogy of works related to her Yupik heritage, at the Baryshnikov Arts Centerbeginning Wednesday. The presentation is part of Performance Space 122’s Coil Festival.

So much has happened between then and now. The usher told Baryshnikov (oh look, it’s Baryshnikov) how much she loves “the space.” The critics clustered on the sidewalk, debating what they liked. (For me it was “the dancing.”) Walking, waiting, talking; waiting, parting, walking. The theater of the to-and-from. The spectacle of everything that, officially, is not one.

I saw Emily Johnson’s The Thank-you Bar in fall 2011 at NYLA. The show began with a walk through the backstage area of the theater, signs mischievously posted along the way with incongruous labels: a white brick wall held one that read “Vaux Swifts nest in this beam.” We entered the stage floor to take one of the 30 seats available in the limited capacity show, sitting either in chairs or cushions on the floor. Our seats, located in the middle of the space, rather than along an edge, meant we were surrounded by the show’s installation, which through its simple construction prevented this immersion from overwhelming. The remainder of the performance—roughly an hour’s worth of interweaving story, music, movement, and light—continued with this intimate yet nimble quality that created a real sense of gentleness that was as soothing as it was powerful.

See if you can you snare a ticket to tonight's concluding presentation of Niicugni--an interdisciplinary, movement-based work by Minneapolis-based Emily Johnson/Catalyst.

Presented at Baryshnikov Arts Center as part of PS 122's COIL fest, the 70-minute work offers rich storytelling through poetic words, movement, soundscape and scenic design--all reflecting the values inherent to Johnson's Central Alaskan Yup'ik heritage.

THE NATIVE PEOPLE OF AUSTRALIA LIVE WITHIN a phenomenology they call Dreamtime. At moments, Dreamtime may encompass the linear time of everyday life, otherwise known as “one-thing-after-another” time. But Dreamtime, or the “all-at-once,” is much more, too: a web in which the culture’s creation stories, generations of ancestors and their influence, and life and death and power co-exist in an infinite confluence of past, present and future.

In Western cultures, we consider our everyday awake time “real” and the hours in which we sleep our time for dreaming. Australia’s native people believe, conversely, that Dreamtime is what’s most real, a state in which all time is simultaneous and in a continual, natural and universal process of creation. All minds participate in Dreamtime, they believe, willingly (consciously) or not.

How do you listen to the quiet? This is no simple question, at least when it comes to describing “Niicugni” by Emily Johnson, choreographer and artistic director for Catalyst. The subtly beautiful and occasionally mystifying work had its local premiere Sunday night at The O’Shaughnessy at St. Catherine University in a co-presentation with Northrop Dance at the University of Minnesota.

Director / Choreographer Emily Johnson talks about Niicugni (nee-CHOOG-nee), the second part of her trilogy that began with The Thank-you Bar.

Why do you refer to your work as "performance installation", as opposed to "dance"?

The work I do is definitely rooted in the body – in dance. But I have a very broad definition of

what that means: our bodies, even in "stillness," dance. There's the blood moving through us, our hearts pumping, our cells dividing and growing and dying, the synapses in our brain firing...so we dance, always. And it isn't performance, but it is (to me), dance. And I think that is a beautiful thing. However, there's this problem with the word, too... it can direct expectations. I don't dislike the word, and sometimes I do use it. It is just not inclusive enough.

My hope is that "performance installation" is inclusive: of dance, of many methods of

communication (visual, aural, architectural, historical, implied), of all forms of performance and

specifically of the performances I make. Installation is really about how I try to immerse a place

and audiences within the context of a particular show. I want to engage many senses: have sound come from all over, offer something you might hold or take care of, something you might smell - it's all to encourage a broad way of paying attention to the place we are in and the people we are near.

Choreographer Emily Johnson speaks with writer/director/actor Ain Gordon about Niicugni, co-presented by Performance Space 122 and Baryshnikov Arts Center as part of COIL 2013.  Niicugni is part 2 of her trilogy of works, which include The Thank-you Bar, winner of a 2012 Bessie Award for Outstanding Performance, and part 3, SHORE, to premiere in 2014. She discusses her research around the act of gathering, her Alaska upbringing, storytelling in performance, the impact of physical land and cultural heritage, and the importance of paying attention.

THE THANK-YOU BAR

“A stunning example of an emerging contemporary American aesthetic…”

—Houston Chronicle

As far as immersive installation performances go, Emily Johnson's "Thank-you Bar" is as disarming as they come. Much of that is due to the light touch of its creator, who has lived in Minneapolis for 17 years but was born in Alaska of Yu'pik descent. Everything about her exudes charisma.

In this work, which started its run at New York Live Arts on Wednesday, Ms. Johnson layers memories and movement to explore ideas about displacement and identity. The title is derived from her grandmother's bar, Que-Ana Bar — the word is Yup'ik for "thank you" — which, for Ms. Johnson, evokes home.

"When I was growing up, it was grandma's house. There just also happened to be these strangers getting drinks at the bar. And we could also sit up there and get Shirley Temples," Emily Johnson said with a laugh. "It is probably still the coolest place."

This was mid last week, and I was sitting in the lobby of New York Live Arts with Johnson and her musical collaborator James Everest, who were finally opening up mid-way through our conversation, having began a bit blurry-eyed due to the fact they'd just finished loading-in the set for The Thank-you Bar (Nov. 9-12; tickets $16 advance/$20 DOS) after a three-day drive from Minneapolis.

"I want to make work that looks at identity and cultural responsibility — that is beautiful and powerful — full of myth and truth at the same time," choreographer Emily Johnson explains in her mission statement. "I want to be grounded in my heritage, supported by my community, and giving back — always." Born in Alaska of Yup'ik descent and based in Minneapolis, Johnson has been creating site-specific dance installations in collaboration with visual artists and musicians since 1998, exploring ideas of home, identity, and the natural world through different modes of storytelling. Her latest multimedia performance piece is The Thank-you Bar, running at New York Live Arts from November 9 to 12. A collaboration with musicians James Everest and Joel Pickard of BLACKFISH, who will play a special set on the final night, the performance installation also includes beadwork by Karen Beaver and paper sculptures by Krista Kelley Walsh.

Anna Marie Shogren, a Brooklyn-based artist and dancer converses with Minneapolis choreographer Emily Johnson about naming, homesickness, and the emotional lives of places. Johnson will perform The Thank-you Bar, named for her grandparents' bar in Alaska, at New York Live Arts this November 9-12.

Anna Marie Shogren: So you've been traveling with this show [The Thank-you Bar] for a few years already?

Emily Johnson: Yes, we premiered in 2009 in Anchorage and then brought it to Homer, Alaska, which is a small town about three, four hours south of Anchorage. We've been to Tulsa and Portland at the TBA Festival; Chicago, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Houston, Vermont, Tallahassee, and now we are coming to New York.

Halfway through the video by Emily Johnson that documents her process and concerns while making the multi-media performance piece The Thank-you Bar, the pace of its narration rapidly shifts. It transitions from a discussion of displacement to her interests in storytelling, specifically oral traditions as they enable a sense of belonging. This shift is abruptly demonstrated through an edit in the video, a sharp pause between images. After a moment her contemplative voice enters and says, "What is becoming more clear to me is what I'm missing."

Emily Johnson was born in Soldotna and grew up in Sterling. She is of Yup’ik descent on her father’s side, from the Yukon/Kuskokwim Delta—Bethel and Akiak specifically. She has family in Anchorage, Fairbanks, on the Kenai, in Bethel, and every two weeks, in Prudhoe Bay. She has lived for fifteen years in Minneapolis and is trying to learn the Yup’ik language. Her personal experiences and questions regarding home/displacement/origin/identity led her to an intensive study of storytelling, writing, and the Yup’ik language during the creation of THE THANK-YOU BAR. She received guidance on storytelling from Kate Taluga, an Apalachicola Creek storyteller in Tallahassee, Florida, and elder Sakim, a linguist who taught her about language histories in relation to displacement histories. She also received mentorship on her writing from Gwen Westerman Griffin, a writer who is Dakota, through the Native Inroads Program at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis.

Somewhere toward the end of the 20th century, many young American choreographers became tired of cool abstraction. Their strategies changed, and they engaged audiences through emotional themes and narratives without abandoning form. Minnesota-based choreographer Emily Johnson is one such choreographer, and her highly personal The Thank You Bar is a stunning example of an emerging contemporary American aesthetic.

Radio Interview with Emily, James, & Joel talking about The Thank-you Bar w/ short live BLACKFISH performance at ODC, San Francisco.

The November performance of The Thank-You Bar, created by Minneapolis dance maker Emily Johnson with musicians James Everest and Joel Pickard of Blackfish, didn't begin inside a theater. Instead, audience members entered a gallery space in the Northrop Auditorium building. The exhibition on view, curated by Johnson with Carolyn Lee Anderson and titled "This Is Displacement: Native Artists Consider the Relationship Between Land and Identity," set the tone for a deeply personal examination of the constants and changes that shape an individual's relationship to home.

"The Thank-You Bar" is designed for an audience of just 50 people and yet it unfolds on the vast Northrop Auditorium stage. Despite the dramatic difference in scale, this project created by choreographer Emily Johnson with James Everest and Joel Pickard of music duo Blackfish delivers a thoroughly intimate and quietly rewarding interactive performance experience.

ONE OF OUR FIRST GLIMPSES OF EMILY JOHNSON, choreographer and co-creator of the luminous new performance piece, The Thank-You Bar, is on video. She's lovely and engaging, even if the words of the story she's telling come not out of her mouth, but from the remove of pre-recorded narration (emanating from a tape recorder tucked in her shirt), and through her facial expressions. Johnson light-heartedly recounts the long and winding tale of a tree, a house, Northrop, and a door in the hallway leading to the Northrop stage that was posted with a handmade sign that reads: "This is a very heavy tree."

There is dislocation in Emily Johnson’s dance performance The Thank-you Bar, but there is no disarray; there is displacement, but there is no rupture. Things are fragmented, but thereby, miraculously, they emerge in a greater whole. The world is broken open, but precisely to understand that it is not broken. History accumulates, but you become distinctly aware that you are experiencing something new.

October smells bittersweet. The month of frost and chills mingles with the sweet aroma of decay and ghostly awakenings.

Fittingly, Out North hosts two art exhibits that cross paths this last week of October, each of them speaking to lost and found souls, to darkness and hope, in its own way. “This is Displacement,” a reflection on the relationship between land and identity by Native artists, closes on Sunday to make room for “Dia de Muertos,” with opens next Friday and runs through November 15.

On the Sterling Highway, near Clam Gulch, an old-fashioned bar made of logs carries a Yup’ik name that’s spelled wrong; mostly to help people pronounce it correctly: Que’Ana Bar.

It means “thank you,” and is the place resting fitfully in the memory of a young woman who visited her grandparents there for many years.

As Emily Johnson grew up, she attended Thanksgivings and Sunday dinners there, and helped process salmon from the family’s nearby setnetting site. In these activities, Johnson was influenced by her Yup’ik grandmother, Hanna Laraux Stormo, who was born in the Kuskokwim region.

What do Clam Gulch, blackfish and experimental dance have in common? How about the latest performance piece, The Thank-You Bar, by choreographer Emily Johnson? Born in Soldotna and raised in Sterling, Johnson spent much of her childhood visiting her Yup'ik grandmother at the bar she owned in Clam Gulch, the Que'Ana Bar. The bar was a hub of activity, including family gatherings, friends, strangers and music. Johnson's memories are filled with the faces and stories of the people who frequented her grandmother's bar.

Growing up Emily Johnson looked forward to spending Sundays at Grandma's. It wasn't just the family, the sourdough pancakes, the country music. It was the ambiance.

"It was a very social place," she said. "It was a bar."

Grandma owned the Que-Ana Bar in Clam Gulch, which doubled as her home. It also was where Emily and her relatives congregated for Thanksgiving, moose hunting expeditions and putting up salmon.

To build a house, you have cut down a tree, leaving any creatures that used to call that tree home shelterless. The house itself becomes home to generations who live in it, love in it and leave it to find a new place to call home. Each being moves on and adapts. But the memory of where they began sticks with them. A sense of longing overtakes them. They feel displaced.

To build a house, you have cut down a tree, leaving any creatures that used to call that tree home shelterless. The house itself becomes home to generations who live in it, love in it and leave it to find a new place to call home. Each being moves on and adapts. But the memory of where they began sticks with them. A sense of longing overtakes them. They feel displaced.

TERRIBLE THINGS

“Prod[s] the boundaries of theater and performance art, working to transform straightforward narrative into something richer, stranger, and ineluctably feminine.”

—The Village Voice

"Let's say anything is possible and everything is happening." This is a line from the newest play by Katie Pearl and Lisa D'Amour, a pair that has been creating performances together for 14 years now. This new work, Terrible Things, follows a largely autobiographical story about Katie Pearl's life, with a particular focus on the thwarting of her childhood dream of being a ballerina, along with a history of her lovers. The metaphor that binds the anecdotes in the show, as well as the idea that the play explores in general, is possibility. Specifically, the notion, borrowed from quantum physics, that because we cannot presently measure the location of a single electron at a given time, that electron can be described as being in all of its possible locations at any specific time. In other words, it's everywhere that it can be simultaneously. This theory is related to theoretical physicist Werner Heisenberg's famous Uncertainty Principle.

According to one interpretation of quantum mechanics, in the course of any event in which multiple outcomes are possible, every outcome occurs—one in this world, others in an array of parallel worlds. So in one world, I might write that I despise Katie Pearl and Lisa D'Amour's Terrible Things and Sibyl Kempson and Mike Iveson Jr.'s Crime or Emergency, both at P.S.122. In another, I might champion one show at the other's expense. In a third, I might never pen a word, as a racetrack win enables me to abandon my career and light out for regions rum-soaked and tropical. But in this world, I will celebrate both shows as appealing and eclectic (and perhaps heave a quick sigh for daiquiris unsipped).

A bunch of bright lights worked on Terrible Things, which you can enjoy at Performance Space 122, now through December 20. Written by longtime partners-in-crime-and-OBIE, Lisa D'Amour andKatie Pearl, choreographed by Emily Johnson, the piece is wonderfully performed by Pearl, Johnson, Morgan Thorson, Karen Sherman and a couple of amiable wrestlers (Rudy De La Cruzand Adrian Czmielewski).

Those Tibetan Buddhists who spend their days toiling over sand mandalas are going about it all wrong—they'd have a lot more fun making marshmallow mandalas instead. Lovers of those gelatinous white sugar puffs will be alternately tantalized and tortured by Terrible Things, a new theatrical dance piece that just opened at Performance Space 122. Upon entering the theater, an army of 1,000 marshmallows are found arrayed on stage in orderly rows. It's a simple pattern, but a hypnotic one, and as the performance unfolds, three female dancers meticulously herd the marshmallows into ever-evolving patterns. Only two are eaten, and none are offered to the audience.

2007

On Saturday I found myself cycling through the drizzling rain to The World Financial Center, an office building on the western edge of the former World Trade Center site. The occasion was Lisa D’Amour and Katie Pearl’s astonishing site-specific performance piece, Bird Eye Blue Print, presented in several rooms in an abandoned office for small audiences of 22 at a time. Upon receiving my ticket in the building’s lobby, I was asked to jot down my “point of origin” on a scrap of paper and wait.

Yes, it looks a little different. This year's list of Austin Critics Table Awards has been slenderized from 51 categories to 37.

So why are there fewer awards if Austin's arts scene has continued to expand?

Because the scene is shifting, not just growing. Creative production across the disciplines — visual arts, theater, classic music and dance — has filled out more equally. The roster of indie galleries and visual art happenings — along with activities at museums — has exploded in the past few years. And local dance producers surprise with ever new ways to intrigue audiences while the classical music scene proceeds at a steady clip.

In a world framed by imminent danger and constant environmental loss, how do people continue to live? Emily Johnson and her Minneapolis-based dance company Catalyst make a complicated stab at creating and populating that kind of anxious world in their evening-length work "Heat and Life," performed Thursday at Gallery Lombardi. With wit, off-kilter, yet aggressive movement, and small moments of simple beauty, the group confronted and nearly overwhelmed its audience.

2006

Emily Johnson doesn’t consider her work “activist art.” Though the endangered natural environment has been her theme in several works, the soft-spoken, slender choreographer and dancer says she owes her vision as much to the exploratory vocabulary of contact improvisation as the natural world of her Alaskan childhood.

As a child growing up in Alaska, choreographer Emily Johnson lived close to nature. She was surrounded by spruce trees and streams, and she became acquainted with Alaska's massive Ice Age glaciers. That experience informs "Heat and Life," a dance about the threat of global warming that Johnson's Catalyst Dance company brings to Dance Theater Workshop next week.

Emily Johnson, a native Alaskan now resident of Minneapolis, brings her all-woman contemporary troupe to New York in Heat and Life, which explores issues surrounding global warming. Multi-instrumentalist JG Everest performs his original score. Johnson and her collaborators have worked all over the west and north, as far as St. Petersburg, Russia; here they make their New York debut. A discussion will follow each performance. Through Sat at 7:30, Dance Theater Workshop, 219 W. 19th

Emily Johnson grew up in the wild open spaces of Alaska. While her U.S. contemporarieswere hanging out at the mall, Johnson was hiking and mountain biking on the KenaiPeninsula. Part Yup’ic Eskimo, she and her family fished from remote beaches,picked cranberries from the local bogs, even hunted moose.

Given the clear skies and balmy breezes last August 27, the Stone Arch Bridge would’ve been packed to the viewfinders even without Landmark - exactly as Local Strategy intended. The interdisciplinary art ensemble’s six members designed their 24-hour celebration of our loveliest pedestrian thoroughfare to enhance its setting, rather than to overwhelm it. They succeeded in every respect, including audience composition. Sure, lots of people turned out specifically for the event’s music, dance, performance art, props, installations, and sundry other free attractions.

This may be the first time wind farms and post-modern dance have appeared in he same story. But choreographer Emily Johnson, 29, finds her inspiration in places where humans, machines and nature intersect. Johnson also likes to self-produce her dance pieces on street corners, in sculpture parks, and in art galleries. So it’s no surprise the “Windfarm” addresses her concerns about environmental degradation.

HEAT AND LIFE (2004)

Shortly after graduating from the University of Minnesota in 1998, Emily Johnson became a presence in the Twin Cities for her rigorous, abstract dance works performed by Catalyst, her company of lithe, tough women. Her choreography was fresh and fierce, evocative and disciplined, her use of staging, costumes, and live music surprisingly mature. Critics hailed the young choreographer as a fresh talent with tremendous potential.

Catalyst, performing "Heat and Life" at a gas station. Emily Johnson's new dance production is about habitat change due to global warming. (Photo by Cameron Wittig, courtesy of the Walker Art Center)

Global warming has received relatively little attention in this year's presidential campaign. For Minneapolis choreographer Emily Johnson, it's a problem that can no longer be ignored or merely 'discussed.' In her latest dance piece, Johnson puts the audience in the middle of a world overheated by global warming.

Emily Johnson is the most exciting young choreographer in the Twin Cities. Since graduating from the University of Minnesota Dance Department in the early 1990's, Johnson, a native Alaskan, has pushed her dance practice into the outer reaches of the form, while maintaining a high standard of artistry. This month she premieres Heat and Life, her newest work of movement, video, and sounds, ant No Name Exhibitions @ The Soap Factory. It will challenge, if not completely transform, your understanding of dance as an art form.

EARLY PRESS

When modern dance wed rock band, nobody expected it to last. But the fine romance between Catalyst and Lateduster proves opposites do, indeed, attract.Couples often form through common friends. Catalyst and Lateduster - a modern dance troupe and ethereal rock band - met through a common fan.

Catalyst Dances by Emily Johnson There's something to be said for a performerwho can put on a pair of pants five sizes too big and dance around to Dolly Partonwith a serious look on her face - and, in the the process, thoroughly convinceus that she has a very bright future. Emily Johnson, of course, doesn't haveto explain what she does. She does most everything with such clear intentionthat we believe - even during the more absurd moments - that she's making perfectsense.

INTERVIEWS

DP: Art and Environment. For the dancer this seems like the quintessential definition of the form. In Heat and Life, you seem to be breaking down this very connection, or that the connection of life itself is breaking. Can you talk about the process in this piece?

Catalyst, performing "Heat and Life" at a gas station. Emily Johnson's new dance production is about habitat change due to global warming. (Photo by Cameron Wittig, courtesy of the Walker Art Center)

Global warming has received relatively little attention in this year's presidential campaign. For Minneapolis choreographer Emily Johnson, it's a problem that can no longer be ignored or merely 'discussed.' In her latest dance piece, Johnson puts the audience in the middle of a world overheated by global warming.

PRAISE FOR Niicugni

"...a fusion of gorgeous dancing, costumes and live music with the spirit, and visual manifestation of the King Salmon. It glitters like the scales of a living fish." - Metro New York

"If you manage to un-guard your heart and pay attention to subtle things--which is what the title, Niicugni, explicitly invites--you will perceive a gracefully-integrated, seductive work of art at the core of which is one rare, exquisite and charming performer, Emily Johnson." - Eva Yaa Asantewaa, Infinite Body

"Before the lanterned darkness empties us back out, let’s take more time to listen to these ingenious muscles, nerves, and bones that channel the migrating fish, the statuesque fox, the eternal swaggering bear." - Siobhan Burke, Performance Club

"Images emerge with the intricacy of dreams. The women hopping and stamping as if the peaty ground has the springiness of a trampoline and vibrating with the thumping, breath-eating joy of their exertions." Debra Cash, The Arts Fuse

"...another of Johnson’s engaging and involving examinations of personal and collective identity and humanity’s responsibility to the planet." - This Week in New York

"[Niicugni] summoned the senses...And Johnson drew upon her deep-felt connections to the natural world to interweave poignant fables, the kind whispered in the middle of the night." - Caroline Palmer, Mpls StarTribune

"Dreamtime is what came to mind. And never left." - Camille LeFebre, MN Artists

PRAISE FOR The Thank-you Bar

"..Emily Johnson's "(The) Thank-you Bar" is as disarming as they come." -Gia Kourlas, New York Times

"...a powerful performance that allows you to see the boundaries of your own aesthetic territory." -Culturebot

"...so delightfully fresh and invigorating, so new, that you want to shout about it from the rooftop and out windows so everyone can know about it...dazzlingly original..." -This Week in New York (twi-ny.com)

"a stunning example of an emerging contemporary American aesthetic" - Houston Chronicle

"She becomes each of us for a moment, as we become her. We lose ourselves for a moment. We discover new selves." - Culture Rover

"Emily Johnson scoops you up and plunks you down in the living, breathing lap of displacement..." - Time Out Chicago

"The beauty and simplicity of the song and story together are transportive. We listeners are alternately cast inside a memory of unbearable heartbreak and the sublime." – mnartists.org

"simultaneously vulnerable and commanding, mythical and wry." - Dance Magazine

"the complex wail of our collective past screamed in a back room somewhere" – Daily News

Audience Responses

"I feel disconnected from my culture. This brings me back."

"By the end of the event, you arrive home, and in arriving home, you also learn about what home is: it’s a familiar place rendered strange, a strange place made familiar; it’s a persistent reminder of something you have forgotten but whose impossible recovery is itself inscrutably comforting. It’s a rustle of leaves."

"Stellar production and performance. The synergy of the music, dance, text, lighting, and staging made for a transformative experience. The use of the theater was brilliant, giving a visual dimension that hauntingly underscored the themes of the work. There were many moments when I felt I was inside a dreamscape, such as Emily's entrance on stilts and all three performers sing Patsy Cline's I Fall To Pieces. I loved the questions/struggles around identity and fear and the silencing effect of racism, which felt authentic not didactic or surface. I loved the stories and use of story and will forever have the image of the melting blackfish in my mind. The dance solo by Emily that happened after the audience turned our seats to face the other way, before Sally joined in, was deeply moving. The gesture of hand to heart and then out, repeated with such intensity, did reach my heart. This work reminds me why I love art." -Eleanor Savage

ABOUT EMILY JOHNSON/CATALYST

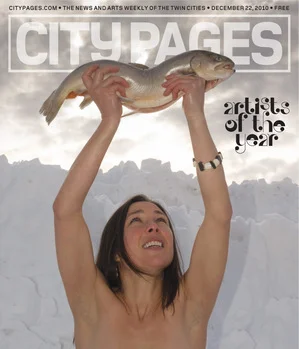

"Emily Johnson, of course, doesn't have to explain what she does. She does most everything with such clear intention that we believe - even during the more absurd moments - that she's making perfect sense."

– City Pages

"Spellbinding"

– The Gothamist

"Uncompromising intensity"

– Gay City News

"Fresh and fierce, evocative and disciplined."

– Dance Magazine

"...a sensibility with remarkable depth and clarity."

– Star Tribune

Sixteen years ago, Emily Johnson moved from her home in rural Alaska to Minneapolis intending to become a physical therapist.

Then dance happened.

She had to drop an overbooked class and needed to schedule another in the same time slot. She chose “Beginning Modern Dance,” then took the next level, and then “Discovery of Improvisation.” It was a life-changer for the young Yup’ik woman, who had always loved the outdoors and sports.