Emily Johnson: A Catalyst for Art, Action & Promoting Indigenous Identity

At a rehearsal for Emily Johnson’s Being Future Being earlier this year, she and the cast decided to wander from Abrons Arts Center, on New York City’s Lower East Side, to the nearby East River Park, where Johnson is involved in protecting 1,000 trees from a demolition project.

As they began rehearsing, trucks rolled up. “All of a sudden, we were having this moment of defending the park through dancing,” says cast member Stacy Lynn Smith. With their path blocked by land defenders as Johnson’s cast continued dancing, the trucks eventually gave up and left.

That wasn’t a performance per se. But it had all the elements that make Johnson’s work and that of her company, Catalyst, so transformational: a quiet power that gathers artists and audiences towards her vision; an uncanny alignment with the natural world; a deep connection to her Yup’ik identity; a disregard for the silos of art versus activism, performance versus protest, dancemaker versus land protector.

Raised in Alaska on Dena’ina land, Johnson grew up not dancing but playing in the woods outside her home, and hunting and fishing with her family. She also played basketball, an early instance of the love affair with endurance that has defined much of her choreographic work.

Her freshman year at the University of Minnesota, Johnson signed up for a modern dance class for fun. Midway through that year, her roommate and close friend passed away unexpectedly. After taking a break from her dance class, Johnson returned to find that students were working on improvisation. As she began improvising, with her eyes closed, “I could see the grief shift away from my body a little bit,” she says. “I remember thinking, Oh, this must be a very powerful form.”

After graduating in 1998 with a dance degree, Johnson began choreographing in the Minneapolis area, with a group of collaborators that would become an early iteration of Catalyst. A clear lineage can be traced back to those early works, which, like her current projects, were concerned with endurance, climate change and Indigenous-centered futures. Her interest in “busting up the idea that the audience is coming into something very precious, or that they’re not involved in” started early too, though in simpler terms—she recalls one piece for which her mother made popcorn from a rented machine and shared it with audience members.

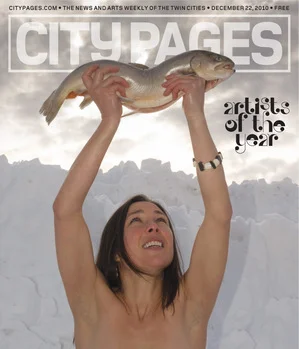

Johnson came to national attention in 2011 with her Bessie-winning immersive work The Thank-you Bar, the first part of a trilogy that included Niicugni, featuring a cast of dancers and community members within an installation of handmade fish-skin lanterns, and SHORE, a multiday event involving dance, storytelling, volunteerism and a feast.

As Johnson’s work has grown in scale, it has also expanded beyond traditional ideas about what performance entails and where it happens. But when her pieces include a meal, or a walk, or an action, these are not peripheral side events propping up the part that is more recognizably dance. To Johnson, they are all equal—they are all performance, they are all dance.

Take Then a Cunning Voice and a Night We Spend Gazing at Stars, her most ambitious piece to date. An outdoor gathering for 300 participants—it premiered on Randall’s Island in New York City in 2017 and has toured to Calumet Park in Chicago—the piece takes place over the course of an entire night and connects moments of dancing, preparing food, eating, storytelling and sewing. When an audience member fell asleep, others would help by providing one of 84 quilts designed by Minneapolis-based textile artist Maggie Thompson. The quilts served as the “home” for the show and were crafted by volunteers from around the world.

In this piece, as in much of Johnson’s work, boundaries between performers and audiences collapse. This is true even in more traditional performance spaces: In The Thank-you Bar, for instance, Johnson slaps the name of everyone in the audience onto her chest with nametags. “Every person watching her work feels seen,” says Rob Bailis, artistic and executive director of BroadStage in Santa Monica, a commissioner of Being Future Being. “Emily collaborates with her audience in a way that very few choreographers do.”

Johnson’s work is at its most transformational when this collaboration with the audience intersects with the radical universes she creates. “For most artists who make that kind of destabilizing work, they intimidate their audiences to the point of not knowing how to be there,” Bailis says. “Emily does that in a way where you feel so held, so trusted and so believed in as a human being that you are drawn all the way into the possibility of seeing things without the structures that cause you to imagine that the world is fixed. She gets such trust from you within minutes.”

The new world Johnson envisions in her work is the same one she is working towards offstage (though to even draw this distinction likely goes against Johnson’s ethos). She has been integral in partnering with institutions in New York City, where she moved in 2014, in decolonial action, including acknowledging the stolen Indigenous land on which their theaters sit. (Today, it has become more common for dance venues in New York City to include a preshow spoken land acknowledgment, a shift that many attribute directly to Johnson’s influence.) She continues to work with several venues, such as Abrons Arts Center, on decolonizing their institutions, and co-leads an eight-month track with Ronee Penoi for presenters on decolonization as part of First Nations Performing Arts, a new initiative focused on capacity building for the Indigenous and non-Indigenous performing arts sector.

Decolonization processes have always been interwoven with her work, and in 2021 Johnson formalized her desire for her presenters to be a partner in not just her dancemaking but her values, crafting a decolonization rider that asks venues to take steps beyond land acknowledgment, such as paying a land-use tax to local Indigenous communities. The rider came to fruition after Johnson penned her “Letter I Hope in the Future, Doesn’t Need to be Written,” detailing her experience with Jedidiah Wheeler, the executive director of Peak Performances at Montclair State University in New Jersey. The letter describes Wheeler’s anger towards Johnson when she asked him to work towards decolonization, and calls Peak Performances “an unsafe and unethical place to work.” It was circulated widely, with scores of presenters signing a statement of solidarity with Johnson.

“I don’t believe that she deviates,” says IV Castellanos, who works as an “InterKinector” on Being Future Being, forging relationships between the artists and communities where the work takes place, with the intention of offering support, amplification and awareness for local land defense efforts and more. Castellanos describes Johnson’s approach to making, creating and gathering as a fusion of care and conviction, giving the example of Johnson requesting that the organizations that invite her think about how every dollar is spent and thus not ask her to stay in a hotel that “funds the pipeline destroying the Indigenous folks’ land that we’re on,” says Castellanos. “A lot of people would overlook that.”

A few years ago, Johnson decided that envisioning a better future through her dancemaking, and working towards it in her activism, was no longer enough. “It started to feel like we need that better future now,” she says. Being Future Being, which premieres at BroadStage this month and tours to New York Live Arts in October, attempts to conjure that future in real time through what she calls “the Speculative Architecture of the Overflow,” which has the goal of building direct response, support and action with local land rematriation and protection efforts. In the work, the quilts from Then a Cunning Voice and a Night We Spend Gazing at Stars become striking “Quilt Beings,” designed by Korina Emmerich, that transform dancers into moving sculptures. Woven into those quilts: thousands of messages from the volunteers who made them, each containing their own vision for the future. As the dancers slowly walk and rotate, the quilts trailing behind them, they could be royalty from another universe. They are literally embodying the future; dancing it into being.